Photo courtesy of Wing-Chi Poon. Licensed under creative commons attribution.

Political complaints about how districts are drawn in the United States date back almost as far as the fall of the British aristocracy – or, more specifically, more than two centuries ago to the fledgling state of Massachusetts.

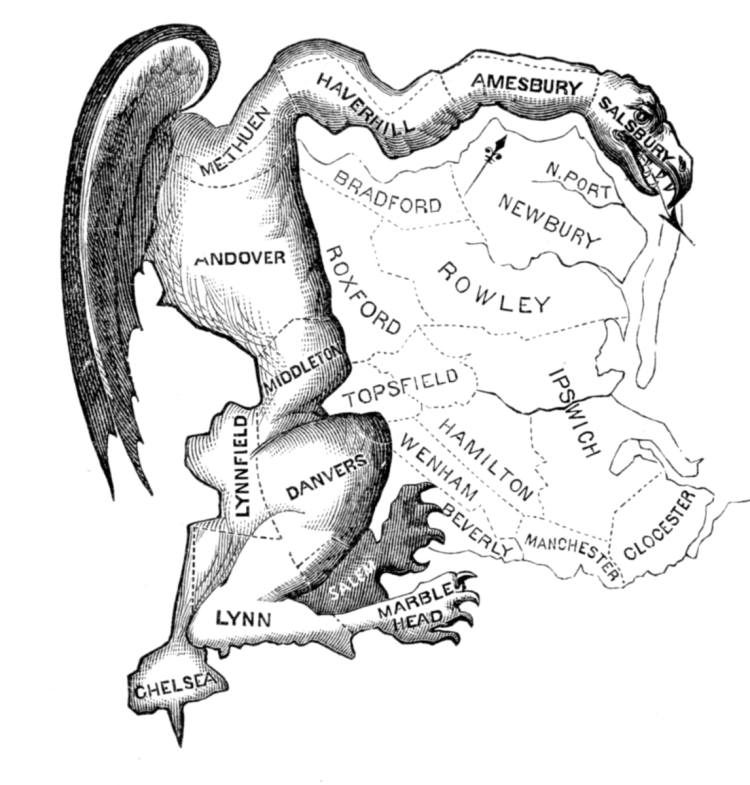

The year was 1812 and Mass. Gov. Elbridge Gerry was seeking a way to draw state senate election districts to benefit his Democrat-Republican party. He passed a bill that approved a map with a number of contorted districts, including a long, skinny one that spawned the north and west edges of the state, mimicking the shape of a mythological salamander.

(Originally published in the Boston Centinel, 1812.)

The portmanteau “Gerrymandering” was coined to mean the actions of one political party to manipulate district boundaries to benefit them.

Fast forward 207 years and politicians are still at it.

As the country becomes more politically charged, the issue of gerrymandering has remained a hot topic as majority parties attempt to seek any advantage to keep power, or minority parties attempt to take back control.

Just this year, the Supreme Court ruled that it is powerless to hear challenges against partisan gerrymandering because it is a political process. That came amidst accusations of gerrymandering in several states, most notably North Carolina, but also Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin.

The political process of redistricting looks different in each state. In most states, the new maps are drawn by the state legislature after each decade’s census and then approved by the governor, making partisan control even more crucial. If a single party controls all three branches of state government, they can usually draw whichever maps they want without giving the opposition any party any say, while a split typically results in a compromise over district maps.

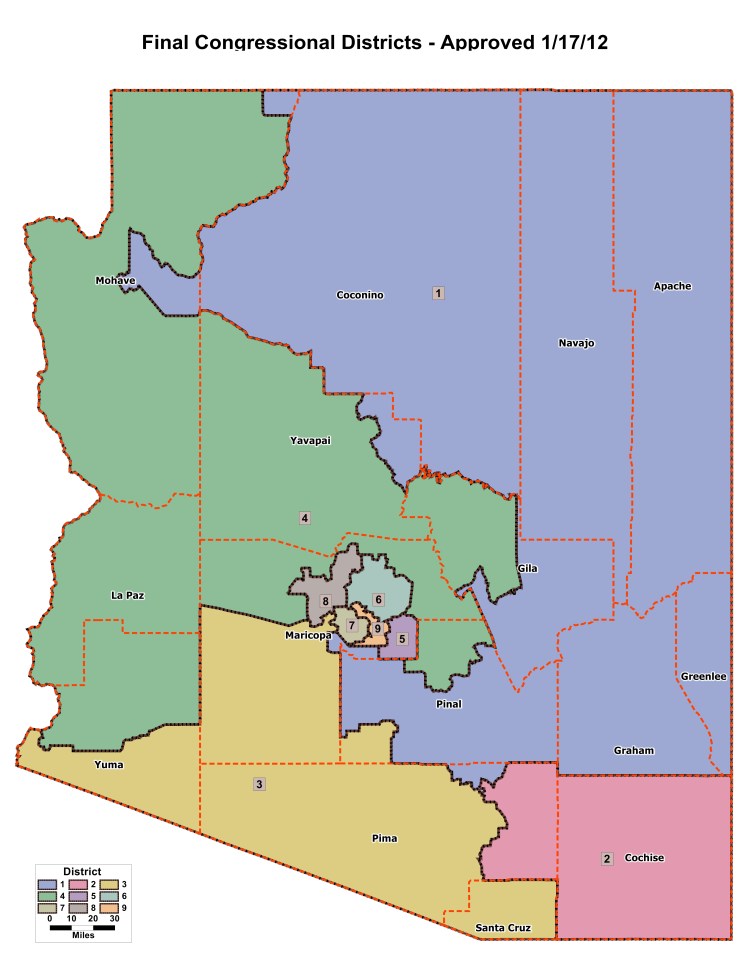

But that process is different in Arizona. The last contiguous member of the United States was one of the first to leave the process in the hands of an Independent Redistricting Commission, thanks to the approval of a 2000 ballot measure. The five-member, bi-partisan group of Arizonans physically draw the map after input from the public, while also adhering to a handful of state and federal requirements for fairness.

(Courtesy of Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission)

While experts say the commission has been effective at eliminating gerrymandering, it hasn’t removed the politics from the process. That’s expected to ramp up even more during the next round of redistricting, as Arizona’s elections become more competitive, and the state is expected to add a 10th congressional seat as a result of exponential population growth.

This project takes a look at Arizona’s history as it relates to political gerrymandering, including the efforts the state has taken to try and prevent such partisanship as it relates to legislative districts, which have produced mixed results, as well as legal challenges to try and hinder those efforts.

It also takes a look ahead to what may happen next decade, when the Republican and Democrat parties are expected to again jostle over the fairness of the state’s map as a result of changing demographics that are going to be highlighted in the 2020 U.S. Census.

The efforts in this project were completed through hours of interviews, historical research of past studies, analyses and news articles, and an analysis of the most-recent elections results using open-source programming that allow users to project state’s legislative maps that adhere to fairness and competitiveness requirements.